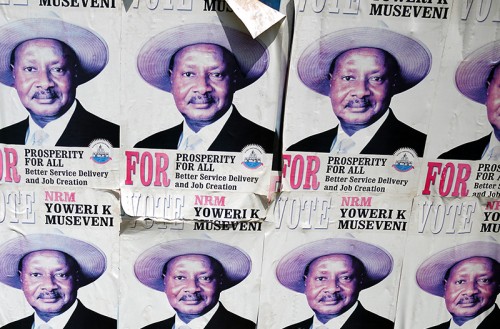

Image: Posters from the 2011 Ugandan elections (Gabriel White, Flickr).

A few years ago I was involved in a research project that looked at state-business relations and economic growth in post-independence Africa. One of our findings was that several African states had been able to grow strongly, for 15 years or more, despite the absence of what most people would describe as ‘good governance’. In states such as Kenya, Malawi, and Côte d’Ivoire, post-independence strongmen, ‘fathers’ of their nations, had presided over strong growth by curtailing multi-party democracy, centralizing economic rents via the patronage system and carving out some space for long-term technocratic planning. We called this ‘developmental patrimonialism’.

While we thought developmental patrimonialism’s achievements in Africa ought to be acknowledged, we also recognized that after less than two decades, they had run into the sand—growth rates had returned to normal, or worse, collapsed. A combination of external shocks and policy mistakes contributed, but we were particularly struck by the economically destabilizing effects of leadership succession. Since investor confidence in patrimonial states is closely tied to a set of personal relationships between political leaders and businesspeople, it is easy to see how the prospect of a new leader taking office might cause growth to fall.

The puzzling thing was that a form of governance that looked rather like developmental patrimonialism had survived for much longer periods in other parts of the world, notably in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, Laos, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam. What made those countries different?

Our subsequent research project found that in most of these cases, authoritarian leadership was embedded in a robust ruling party with consensual decision-making procedures, and conventions governing leadership succession. Investor confidence was tied more to a set of relationships with an entire party, than, as in the case of Africa, to a particular leader. (The main exception here was Indonesia, where President Suharto had failed to solve the question of succession, failed to build a strong party, and where growth had plummeted alongside his demise.)

Our findings were consistent with a wider body of quantitative research which found that growth was more stable in ‘institutionalised’ than ‘personalised’ autocracies. It is these more institutionalized states that have earned autocracies a (disputed) reputation for being superior promoters of economic growth. When we add the more personalized regimes into the equation, however, autocracy’s record is no better than democracy’s.

So what did this mean for other relatively personalized autocracies, ‘developmental patrimonial’ regimes such as Uganda and Angola in Africa, or Cambodia in Asia? Were these successful growth experiments doomed to fail when one leader gave way to another, or was there a possibility that these regimes could become more institutionalized, without necessarily becoming more democratic?

In a recent piece of scoping research for DLP, I tried to shed light on this question by looking at all those autocracies that had on average grown at 3% each year for a continuous 20-year period between 1960 and 2010, and experienced a change of leader. Those countries were:

- China (1968-2010)

- Egypt (1976-2010)

- Lao, PDR (1979-2010)

- Mexico (1961-1980)

- Morocco (1961-2010)

- Republic of Congo (1961-1990)

- Syria (1961-1980)

- Vietnam (1989-2010)

Of these, Laos, Mexico and Vietnam were institutionalized party states of the kind already described, and, interestingly, they became institutionalized before embarking on their high growth episode. Morocco is an institutionalized monarchy, while Syria is probably best described as a quasi-institutionalized party state with dynastic tendencies. The Republic of Congo is a case where authoritarian leaders repeatedly tried and failed to build an institutionalized party state, but in which oil revenues kept growth strong. In fact, the only two conceivable cases of high-growth personalized autocracies becoming institutionalized authoritarian states are China (under Deng Xiaoping) and Egypt (under Anwar Sadat).

What does this tell us about the prospects for today’s developmental patrimonial regimes?

The first thing is that the institutionalization of authoritarianism, at least among high-growth countries since 1960, has been very rare. Personal rulers tend to govern by deliberately keeping institutions, and rivals, weak. To suddenly start strengthening institutions instead of weakening them requires, then, a remarkable change of tack, and the old adage that a leopard cannot change its spots seems apt here.

Further, in both Egypt and China, greater institutionalization was introduced following the death of a charismatic revolutionary leader, by new leaders who needed additional sources of legitimacy. The geopolitical context of the time, being more sympathetic to dictatorship than today’s, gave them some breathing space. Indeed, China’s considerable power and party traditions made it immune to outside forces that might want to establish liberal democracy within the country.

To date, the likes of Yoweri Museveni and Hun Sen have shown little inclination to eschew their personal power networks in favour of a more institutionalized form of rule. Besides, there is nobody of Deng’s stature waiting in the wings to take these ruling parties to another level (and even if there were, the international community is unlikely to be supportive).

So, when these leaders finally leave the scene, they seem most likely to be replaced either by a more vibrant form of multi-party democracy, or by another personalistic autocrat. I consider the conditions under which the former is likely to lead to sustained growth in a new DLP paper. As for the latter, there has been speculation that both Hun Sen and Museveni would like to transfer power to members of their own families. While dynastic succession was a common means of escaping developmental patrimonialism’s dead-end in early-modern times, it remains to be seen whether it can work in the 21st century.

For more on Tim’s new paper, see his post How can a high-growth autocracy become a democracy without derailing growth? (28 Sept 2016)